On 1 August 2017, BuildCert – the product certification programme for plumbing products – changed its name to NSF International. Here, Francine Wickham, global marketing director at Fernox, explains the testing process for chemical inhibitors and what the rebranding of BuildCert will mean for the industry.

Founded in 1998, BuildCert is a provider of mechanical and materials certification services for the plumbing and building industries, including the Chemical Inhibitor Approval Scheme (CIAS). Whilst established in the UK – with Fernox as one of its original founding members – the BuildCert logo and services have a global reach, representing quality and high-performance.

Chemical inhibitors: the testing process

Chemical inhibitors are essential to maintaining a central heating system and are consequently included within Part L of the Building Regulations for Conservation of Fuel and Power. In addition, boiler manufacturers often require a BuildCert-certified inhibitor to be administered for the boiler warranty to remain valid.

To ensure chemical inhibitors meet minimum performance requirements, manufacturers, test laboratories and BuildCert worked together to develop CIAS, a minimum performance standard to guarantee the quality of chemical inhibitors. Having been adopted by the industry it is seen as a quality benchmark by manufacturers and third-party certifiers. As such, CIAS testing is now strongly recommended for all chemical inhibitors.

Requiring re-certification every five years, chemical inhibitors are tested to show that; they restrict the formation of calcium-based scale, are compatible with non-metallic elements found in central heating systems and reduce metal corrosion. Only if the product passes all three tests, will it receive certification.

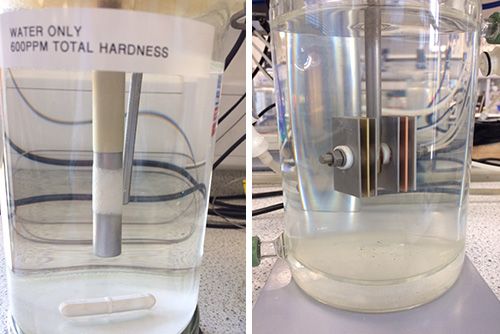

To measure the impact of a chemical inhibitor on the level of metal corrosion, copper, brass, mild steel, stainless steel and aluminium coupons – the metals traditionally found in central heating systems – are submerged in the test solution. Once submerged, the solution is heated to 82°C to mimic the conditions of a central heating system. By measuring the weight loss of each of the metallic coupons the laboratory can obtain the corrosion rate.

This test is run in duplicate in hard water, soft water and naturally aerated and aerated conditions (where extra air is bubbled through the water). If the corrosion rate for each metal is under its specific limit, the product passes.

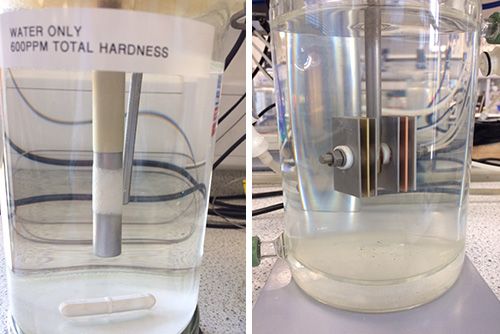

To measure the effectiveness of a chemical inhibitor on reducing calcium-based scale, a heating stick heats the solution to the same 82°C as required in the corrosion test. The liquid is heated for seven days, before the amount of calcium remaining in the water is tested. If the level of calcium is similar to the starting level, the inhibitor passes this test. If there is a drop-in calcium, it means the calcium has formed solid calcium carbonate (limescale).

Finally, the inhibited solution undergoes a non-metallics test. Representing the non-metal part of a central heating system, squares of various rubbers are submerged into a double dose of the test product. One complete, the rubber is weighed both dry and wet and observed for any abnormal swelling or weight gain. Again, if the levels are within the boundaries of acceptability, as set out by the CIAS, then the inhibitor is certified.